Grammar at Work and School, Part 1: Why 97% Think It Still Matters

I spent my 7th grade mornings with one of the last of an endangered, now virtually extinct, species. By the time I arrived at her Language Arts/Social Studies class at Roland-Grise Junior High in Wilmington, NC, Dorothie Ashley was already ancient, with coke-bottle-thick glasses and thicker skin from decades of experience dealing with ‘tween hormones. (Mrs. Ashley’s age was a source of intense speculation by us. Our median guess was 90.*) Her passion: the dying art of… GRAMMAR.

Dorothie Ashley at work in 1971. Despite lingering PTSD (Painful Trauma from Sentence Diagramming), I learned a lot from her. (Photo Brad Kutrow)

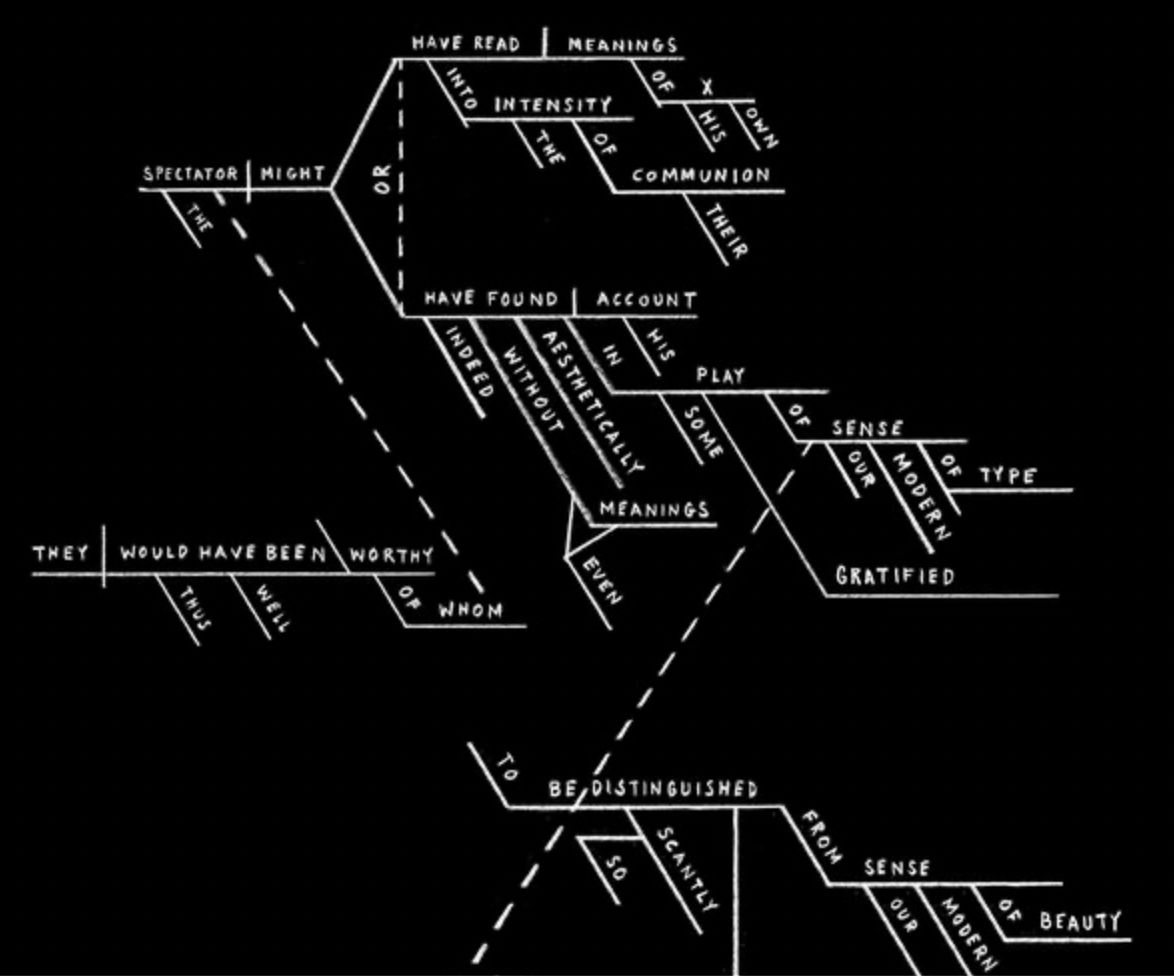

It’s possible we read a book that year in her class. I know I wrote a term paper, supposedly about the government of Japan, in which I focused instead on the adventures of a North Carolina-based Olympic skier during his visits to geisha houses. But mostly I remember diagramming sentences, everyday – at our desks, using fountain pens filled with jet black ink (it took me two years to wash all the smudged ink out of the heel of my left hand), and at the blackboard. We identified sentence patterns, drew lines and ladders for parts of speech to perch on and hang from. And slowly, painfully, we got to the point where we could depict every word in the longest sentences somewhere on the grids we built. We became grammar gurus. The Prime Directive, from the woman we called, affectionately, Gramma, was “Know the rules. Never break the rules.”

Diagramming complicated sentences is fun in the same way dental surgery without anesthesia is. But it does teach you grammar.

Ten years later, when I found myself teaching agrammaric 9th graders in Lynchburg, Virginia, I had to make an uncomfortable call. Would I do to them what Gramma had done to me?

Yes I would.

I spared my students the jet black ink and fountain pens and cut down a bit on the grammamania, but we diagrammed. I tried to make up fun sentences so it would be less painful, but I don’t think they loved it any more than I did.

Their best pushback was this: “Why do we have to learn this s***? You know what we mean.”

I didn’t have the gravitas to make my own Prime Directive. The best I could come up with was a series of practical arguments:

· Improving Clarity: Sometimes if you don’t use grammar correctly, people will actually be confused by what you mean, or it will cause them to slow down and stop paying attention to what you are trying to say. Make it easy for them to understand you.

· Avoiding Judgment: Sometimes other people may understand what you mean, but will be thinking to themselves that you said it incorrectly. A Tidio survey found that 96.5% of people (even 87% of Gen Z’ers) said grammar mistakes affected their perception of other individuals (even though only about 3% of them were able to catch all the mistakes in a sample quiz). Some 97% said they downgraded their opinion of companies if they saw grammar errors in corporate communications. Other research suggests that hearing bad grammar can trigger physical distress in the people who hear it, including dilating pupils and rising heart rates. You can argue that shouldn’t be the case, but some people are going to judge you for the way you talk or write. Don’t give them that opportunity.

· Avoiding Paranoia: A lot of us get nervous when we aren’t sure of the correct way to say something. One of the most common manifestations of atelophobia, the fear of making mistakes, is with grammar. We aren’t sure, so we freeze and sweat. Save yourself the angst.

· Language Bonus: If you want to learn a foreign language, you’re going to need to learn these rules anyway. Why not just learn them in your native language now?

My years working in television and radio, and, later, in places requiring public communications, have taught me a few things. First, as a reporter you will never, ever get away with a grammatical error – someone will always call suggesting you be fired. Second, using technically correct grammar can sometimes interfere with communication – it can sound so weird to folks that they don’t pay attention to what you are saying. And, third, language and the norms around it continue to evolve – it’s probably time to give up on some of the “rules.”

You may be thinking you don’t need to know any of this stuff, that this is why we have programs like Grammarly, websites like Quillbot or forums like Reddit to help us resolve our questions. But none of those sites address the blind panic moment when we can’t turn to those sources. We start to utter a sentence in the middle of a Zoom call, or during a presentation, or face-to-face in a conversation with a colleague or client or friend or child — and freeze.

In those moments, this is my variant on Mrs. Ashley’s Prime Directive: Know the rules. Then you can decide when to break the rules.

So the next two posts are going to highlight a few especially tricky grammatical problems we face in those deer-in-headlights moments. I’ll describe what the grammatical rule is. Then I’ll share my opinion on whether I think the rule still “matters.” If I think it does, I’ll offer ideas for how to avoid sounding like a snob while communicating your ideas.

There is no writing exercise that makes me feel more vulnerable than writing about grammar. I expect (and welcome) you to point out the grammar and punctuation errors I make in these and all subsequent posts. (Yes, I overuse parentheses. I occasionally abuse the pronoun rules for emphasis. I love me some sentence fragments. Seriously. I’ll swap dashes and colons with impunity: it’s who I am — it’s what I do. And I love starting sentences with “and” and “but.” Guilty, guilty, guilty, guilty, guilty.) I know grammar purists will be outraged about the rules I’m giving up on. And I’m trying my best not to imagine what Mrs. Ashley would think of her fallen student. But I hope you’ll join me for the ride.

-Leslie

*PS: Shocking fact check: according to her obituary, Mrs. Ashley was exactly my current age when she was teaching me in 7th grade. Was she young or am I old?

Coming up in Parts 2 and 3:

Part 2: Pronouns and danglers: Between you and me, the rules related to these are important.

Part 3: Sentence fragments: All bad? The subjunctive: If only it were more common. Word pairs we confuse: I pick six. Should I be less restrictive or pick fewer pairs? And some omphaloskepsis: when should we use big words?

Notes:

On the merits of diagramming: https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/06/18/taming-sentences/

Tidio survey of grammar paranoia: https://www.tidio.com/blog/common-grammar-mistakes/