Grammar at Work and School, Part 3: Would That It Were That Easy

Since 1973, there have been several attempts to revive Grammar Rock. It’s never quite worked.

If you had to pick the zenith of grammar in the US zeitgeist, it would have to be the way-cool series that debuted on children’s TV in 1973, Grammar Rock. Part of the Schoolhouse Rock series, Grammar Rock tried to make it fun for young’uns (and interesting for adults) to learn grammar by having real jazz musicians do the music. If you’re of a certain age, you can probably still hear the voice I recently discovered was a guy named Jack Sheldon, sounding like a cross between Joe Cocker and Louis Armstrong, singing this hit song from the series: “Conjunction junction, what’s your function? Hooking up words, and phrases and clauses.”

Ever since, we Americans have breathed a collective national yawn on the subject. A lot of folks still vaguely care about grammar, but it’s not something we like to talk about. And it’s definitely not cool.

I’m doing this series anyway. In Part 1, I made my best case for knowing a few of the basic rules of grammar to help you at work and at school. In Part 2, I took up a couple of tricky grammar challenges I think it’s good to get right. In this final part I’ll take up a few more you’ve asked me about, as well as another complicated question we all face from time to time – when do we use big or uncommon words?

Here we go…

Challenge #3: How big a deal are sentence fragments?

If you want to write a real sentence, you should make sure it has a subject and a verb. But both don’t always have to actually appear in the sentence. Sometimes you have an implied subject or verb.

{Did you} Get that?

{Are you} Ready?

{Now you get} Set!

{You} Go!

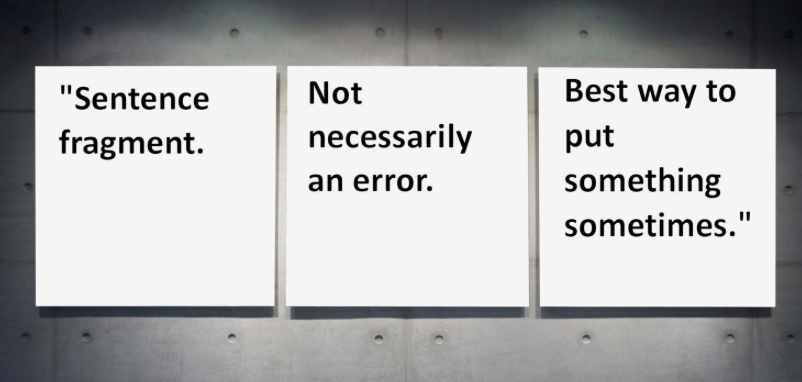

At other times you might use a sentence fragment to break up the monotony of a series of similarly-constructed sentences or to catch people’s attention.

Makes my point. Seriously.

My opinion: Know the rule. Know the audience for whom you are writing and whether they will care. Then break it if you want to.

Challenge #4: Which of these two tricky words do I use… and when?

Among/between – The easiest rule to remember here is that you use “between” when you are talking about two things (“I had to choose between writing this piece and writing a post about sports betting”); you use “among” if you are talking about more than two (“Among the readers of boneconnector.com, six countries are represented.”).

That said, there are a ridiculous number of examples where “between” is commonly being used to apply to more than two things. (“He zigzagged between the cars,” etc.).

But please get this one right: you should always say “between you and me” – not “among you and me” (and definitely not “between you and I” — see Part 2 on pronouns).

My opinion: Worth paying attention to if you are writing formally; not a biggie in normal conversation.

Less/fewer – I made this mistake more than any other when I was working in journalism. After I screwed it up repeatedly, one editor eventually beat me up enough that I learned.

I think we all want fewer problems and less trouble using “fewer” and “less.” The easiest way to remember the rule is that you use “fewer” when something can be counted; “less” when you are talking about a hard-to-count quantity.

Remember that Toby Keith song, “A little less talk and a lot more action”? Less talk is not a specific number of sentences; it’s just a smaller total quantity. The old marketing slogan for the Marines was “The few. The proud. The elite. The Marines.” Marines can be counted. There are fewer of them than there used to be.

The rule is helpful but not absolute – grammarians seem to accept that some items cost “less than $20” and I describe some of my posts as being “1000 words or less.”

My opinion: Good to know for formal use.

That/which – This is one of those that most of us just guess on. Use “that” when the information in the clause it introduces can’t be omitted without changing the meaning of the sentence (“The column {that I wrote about obscure world championships} was brilliant”). The information included inside a “which” clause may be interesting, but is not the central point of the sentence (“The tofu, {which I made}, was tasteless.”

My opinion: I no longer care much about this one.

Affect/effect – Affect is usually a verb meaning “to influence” (“The winter weather affected my mood.”), whereas “effect” is usually a noun referring to the result of something (“The winter weather had a big effect on my mood.”).

Just to make it confusing, affect can sometimes be a noun referring to emotion (“She had a flat affect”) and effect can sometimes be a verb meaning “cause” (“Leslie’s column about grammar effected a change in the number of subscribers.”), but in general it’s useful to know influence/result.

My opinion: So many people are so confused about this distinction that it is probably worth learning.

Like/as –There’s lots of nuance here, but the key distinction is probably that you should use “like” when you are talking about similarity (“I whistle like a bird”) and “as” when referring to roles (“He worked as a WWE referee”). You are not supposed to use “like” as a conjunction – officially correct usage would be “Nobody writes about grammar like as I do.”

My opinion: As a person who has thought a lot about this case, I, unlike some grammarians, won’t die on this hill.

Their/they’re/there; your/you’re/ur; it’s/its: If you are fuzzy on these pronouns that sound the same but are spelled differently and mean different things, just remember that “their” and “your” are for when you are referring to possession – “Their tails were between their legs” or “Your arms are too short to box with God.”

“They’re” is a contraction of “they are”; “you’re” is a contraction of “you are.” “There” is used as an introductory pronoun (“There is a balm in Gilead”) or as an adverb for location (“Our team is over there”).

“UR” in text originally meant only “you are” or “you’re,” but now sometimes also means “your.” “It’s” is always a contraction for “it is” (“It’s the dawning of the age of Aquarius”); “its” is a possessive pronoun. (“The turtle retreated into its shell.”)

If UR consistently struggling with which pronoun form to use for the ones that sound the same, you’re going to be better off if you use your grammar app.

My opinion: Most of us know the distinctions between these, but we just get in a hurry sometimes and get sloppy. If you think it doesn’t matter, the Tidio survey I cited in Part 1 found folks thought this when they saw folks mix up “their,” “they’re” and “their”: 53.1% thought it was careless; 22.4% thought the writers were uneducated; and 20.7% thought the writers were incompetent.

Challenge 5: Does anybody still care about the subjunctive?

If you know the word “subjunctive,” it’s probably from learning weird tenses in a foreign language, not from studying English. Unlike the romance languages, English doesn’t have a specific subjunctive tense; we just have a “mood.” And we rarely use it.

The subjunctive mood allows you to express wishes, hypothetical ideas and outcomes, and it uses unexpected verb forms.

· “What would be your suggestion to me for my first day at your company?” “I’d suggest that you be on time.”

· “If I were the king of the forest, I’d command each thing with a royal growl.”

He was only hypothetically the king of the forest, but the Cowardly Lion did know how to use the subjunctive.

My opinion: Those are about the only two kinds of cases where the subjunctive causes people trouble in English. Learn those and make a call about whether you use them. If you think correct use of the subjunctive sounds too pretentious, I’d suggest the same approach as for pronouns above. Rather than saying it incorrectly (“I’d suggest that you are(be) on time” or “If I was(were) in your shoes”) find a workaround (“Show up on time” or “I’d rule the forest with a growl.”).

Bonus Challenge 1: Punctuation after closing quotation marks

I’m adding this one at the request of two different readers because the rule is both illogical and varies based on whether you live. In the US, always put a period or comma before a closing quotation mark (in Great Britain it always goes outside the closing quotation mark). Whether a question mark or exclamation point comes inside or outside the closing quotation mark depends on whether the question or exclamation is part of the quote or not. The punctuation in each of the following sentences is correct:

· “Play more disc golf,” he said.

· “My power has been off for the past five days,” Gerd complained, “but I’m still going to eat this hamburger meat.”

· “What is this thing called ‘love’?” she wondered.

· Did you notice how often Leslie uses the word “omphaloskepsis”?

· “I’m so excited this is the last post about grammar!” said Serge.

My opinion: It doesn’t make much sense that we would use different rules for periods vs. question marks, but who said life (or punctuation rules) would be completely logical?

Bonus Challenge 2: When do we use big words?

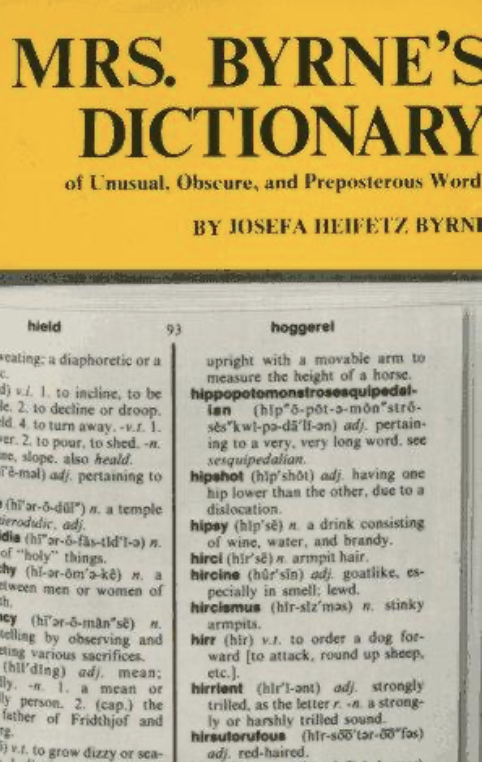

There’s one other grammar-adjacent rule I think is worth mentioning. It’s the problem of big words. Part of my first job in radio was doing a daily, one-minute segment called, with faux seriousness, “Word of the Day!” It was an excuse for me to share fun, interesting and sometimes absurd words. Among my favorites: “hippopotomonstrosesquipedaliaphobia” (the fear of really, really long words) and “omphaloskepsis” (the act of gazing intently at one’s own navel).

If you love big or strange words, Mrs. Byrne’s Dictionary could be your jam.

My opinion: It can be really fun to learn a new word and show it off to others, but I think the key question you need to ask yourself is whether using it will communicate what you want it to.

Will the person understand what you meant? If they don’t, will it make them feel bad about themselves, or will they think you’re a snob? (yes, “hirsutorufus” is a fun word, but it adds no additional information to your description of Ron Weasley — just say “red-headed”) When I was in broadcasting, you didn’t want anyone to be distracted trying to figure out what a big word meant; you wanted them to immediately understand you. In print, you have more latitude: if you really believe the big/unusual word is the perfect one to help you make your point, keep it in and give your reader a chance to look it up!

*******

So there they are: my big five rules (plus two bonus rules) about grammar and word usage and punctuation that I think are worth knowing. As I’ve noted throughout, it’s up to you whether you want to follow them or not. I won’t judge you. But now you’re prepared for the people who will!

-Leslie

A request: Can you share your most embarrassing or triumphant grammar moment?

Notes:

Tidio survey: Tidio survey of grammar paranoia: https://www.tidio.com/blog/common-grammar-mistakes/

Mrs. Byrne’s dictionary is a great source of obscure words: https://www.awesomebooks.com/book/9780586206003/mrs-byrnes-dictionary-of-unusual-obscure-and-preposterous/used

Conjunction junction video: https://youtu.be/UVpLpGzG-EU