AI and Jobs Part 3: “Steering” AI With Policy

A few weeks ago I looked at the growing evidence that the AI revolution will radically change the way we work, and sooner than we had been expecting, especially for younger people trying to enter the workforce.

A lot of you got upset that the piece was too bleak, so I wrote a followup trying to imagine which “old” jobs were likely to survive and which “new” jobs might spring up in a world where both AI (which is disproportionately threatening white collar jobs) and automation (a bigger threat to blue collar jobs) continue to grow. I picked out seven categories that seem proportionately “safe” as we move forward.

There are no Neo-Luddites with the power or argument to stop the relentless march of AI and automation through the job market — we like the promised of added convenience and efficiency and profits too much to argue.

But if we don’t want to — or can’t — get in front of the ship and stop it, we may have another move. Dario Amodei, the CEO of AI giant Anthropic, says we may be able to “steer it 10 degrees in a different direction from where it was going. That can be done. That’s possible, but we have to do it now.”

We can’t stop the AI ship, but we may be able to nudge it in the right direction. (Illustration using AI from deepai.org)

This piece looks at the role government, educational institutions, companies and even the faith community might play in “steering” while the world of work is reinvented. For each group, there is both an obvious policy path and another that is less obvious, but more important.

Government and AI policy

The default policy path: So far government has followed an obvious AI policy path, articulated by Marc Andreessen and Sam Altman: one designed to help the industry develop as quickly as possible in the US. “The single greatest risk of AI,” says Andreessen, “Is that China wins global AI dominance and we – the US and the West – do not.” Altman notes that the question is whether the AI race is won with an American “democratic vision” or an “authoritarian” vision. This “technological security dilemma,” writes Robert Bellafiore in the New Atlantis, suggests that “even if all of AI’s speculated downsides were to come about – mass unemployment, retreat into delusional virtuality, learned helplessness among all those who can no longer function without ChatGPT, and so forth – we would still need to accelerate AI to stay ahead of China.”

To help reach that goal, the federal government, states and municipalities have provided huge tax incentives for construction of energy infrastructure and data centers and have mostly avoided regulations on AI: an early version of the “One Big Beautiful Bill,” prohibited states from passing any restrictions on AI development for the next 10 years. The Senate ultimately rejected that provision, but so far there, because of the fear of China, discussion about AI’s impact on jobs and privacy have been muted.

An alternative policy path: It doesn’t have to be either/or. Government can be concerned about China while actively working to prepare for the massive restructuring of the job market that AI and automation are bringing.

· We should be exploring -- now -- the question of who pays and how when companies use AI to downsize their workforce. Are the newly unemployed on their own to figure it out? Does government pay for retraining without a new source of revenue? Or should there be “token taxes” on AI companies, or companies using AI, as Amodei has suggested, to be used to retrain or support those who lose their jobs to AI?

· What does “retraining” look like in an AI/automation-centric economy? Our current “workforce” system is heavily tilted toward lower-income workers. What happens as AI and automation double team to eliminate jobs at the high and low end of the spectrum?

· What do we “retrain” people to do? If we can be confident that the US will face a massive deficit in skilled tradespeople over the next twenty years, how can we do a more effective job at convincing more people to consider these jobs? What would a new robust apprenticeship initiative look like? And if tech optimists are correct in their prediction that more new jobs will be created by AI than eliminated, how do we prepare people for those jobs?

· If there is even a 10% chance that we are heading toward 10-20% unemployment in the next five years, as Amodei predicts, or that AI will eliminate 50% of current white collar jobs, as Ford CEO Jim Farley has suggested, shouldn’t we be doing the background work to explore how a “universal basic income” or some other approach for the long-term unemployed might work?

Education and AI policy:

The default policy path: After initial outright bans on using AI to try to crack down on cheating, schools appear to be moving, slowly, toward an approach of “managing” AI use, teaching students to use it more appropriately and effectively.

On a grade school level, administrators are beginning to embrace AI’s potential to free up teachers for more personalized interactions with their students. The Miami-Dade school system is making Gemini AI available this fall to 100,000 students. Using grants from Microsoft, Open AI and Anthropic, the American Federation of Teachers is setting up a training hub for teachers nationally to learn how to more effectively use AI in grade school instruction.

On a university level, a 2025 study of teachers in 28 countries found that currently 39% of university faculty have begun integrating AI into their courses, with half of them directly teaching students how to use and evaluate results. Still, just 9% of university chief technology officers believe universities are ready to respond to AI. Students, meanwhile, have been quicker to adopt; about 90% of them say they are already using AI to complete assignments.

Expect most universities to go all in on AI, but there’s also an opportunity to go all in on humanities.

If you look at university websites now, it’s pretty clear you can expect more and more embrace of AI. There will be core courses about AI, much more widespread use of AI tools, personalized AI tutors and counselors and more emphasis in general on digital literacy. Administratively, schools will be using AI in the same ways as other corporations: for hiring, HR, procurement, travel, etc. Open AI is encouraging universities to distinguish themselves through branding themselves as “AI-native.” The first to sign on: the California State University system, with 460,000 students.

An alternative policy path: learn more about being human Understanding the basics of AI and how to use may soon become a basic form of 21st century literacy.

But what will truly distinguish the students of the future is their ability to answer a question Scott Galloway asks: “What would make me irreplaceable?” They will need to learn to think in ways that, for the forseeable future, a computer, even an ever-smarter AI, can’t.

As the speed of change accelerates, educators need to find ways to raise up more students who are ready not to fall into jobs for life, but to think entrepreneurially about their career paths.

· We’re going to need more people with the ability to identify new possibilities for themselves, and the habit of mind to reinvent themselves again and again.

· We need to teach them to see connections between disparate ideas and subjects, to make wild connections across fields based on observations of nature, of human interactions, of music or dance.

· We need them to learn to tell stories and feel empathy with others. It might be time for a revival of the kind of thinking one learns in “the humanities.” It’s not clear that students can learn those deeply human thinking skills with AI — will universities need to set up AI exclusion zones to give students a chance to learn to do that kind of thinking?

The corporate community and AI policy:

The default policy path: It’s one of the first things business school students learn: the goal of a corporation is to maximize shareholder value. When companies apply that “value” narrowly, it will always lead to more automation and greater use of AI. As Charles Camosy and Mariele Courtois argue in a recent article in The Atlantic, “Left unregulated, markets will continuously choose efficiency at the expense of workers, risking widespread unemployment and the dehumanization of the kinds of work that manage to survive.” In the near-term that will maximize efficiency and shareholder value.

An alternate policy path: While much of the backlash for the impending job loss will fall on politicians, companies doing the layoffs risk losing significant reputational capital if they don’t handle their layoffs and downsizings carefully. And that has the potential to erode shareholder value.

Companies looking to manage the transition should consider:

· Exploring all strategies that use AI and automation to augment rather than replace employees, with substantial proactive retraining efforts offered to employees prior to layoffs.

· Considering the ways that being more “human forward” might distinguish them from competitors, especially in fields like sales and customer service.

· If companies are replacing the work currently done by entry-level workers, rethinking how they bring on new talent. What would a white collar “apprenticeship” look like in an AI world?

· When downsizing employees, work closely with government and other services to ease the transition, offering retraining onsite. And since the length of unemployment is likely to be longer, companies should use the increased profits from their “efficiency bump” to contribute to unemployment services at higher rates.

The faith and nonprofit community and AI policy:

The default policy path: The traditional role of the faith and nonprofit community in times of crisis is to be responsive when bad things happen: in times of mass layoffs, these institutions provide comfort and support for those going through transition. The upcoming challenge will provide new opportunities for religious organizations, job training centers, legal aid offices, housing assistance centers, counseling offices and others to provide hope, inspiration and options to their followers and clients.

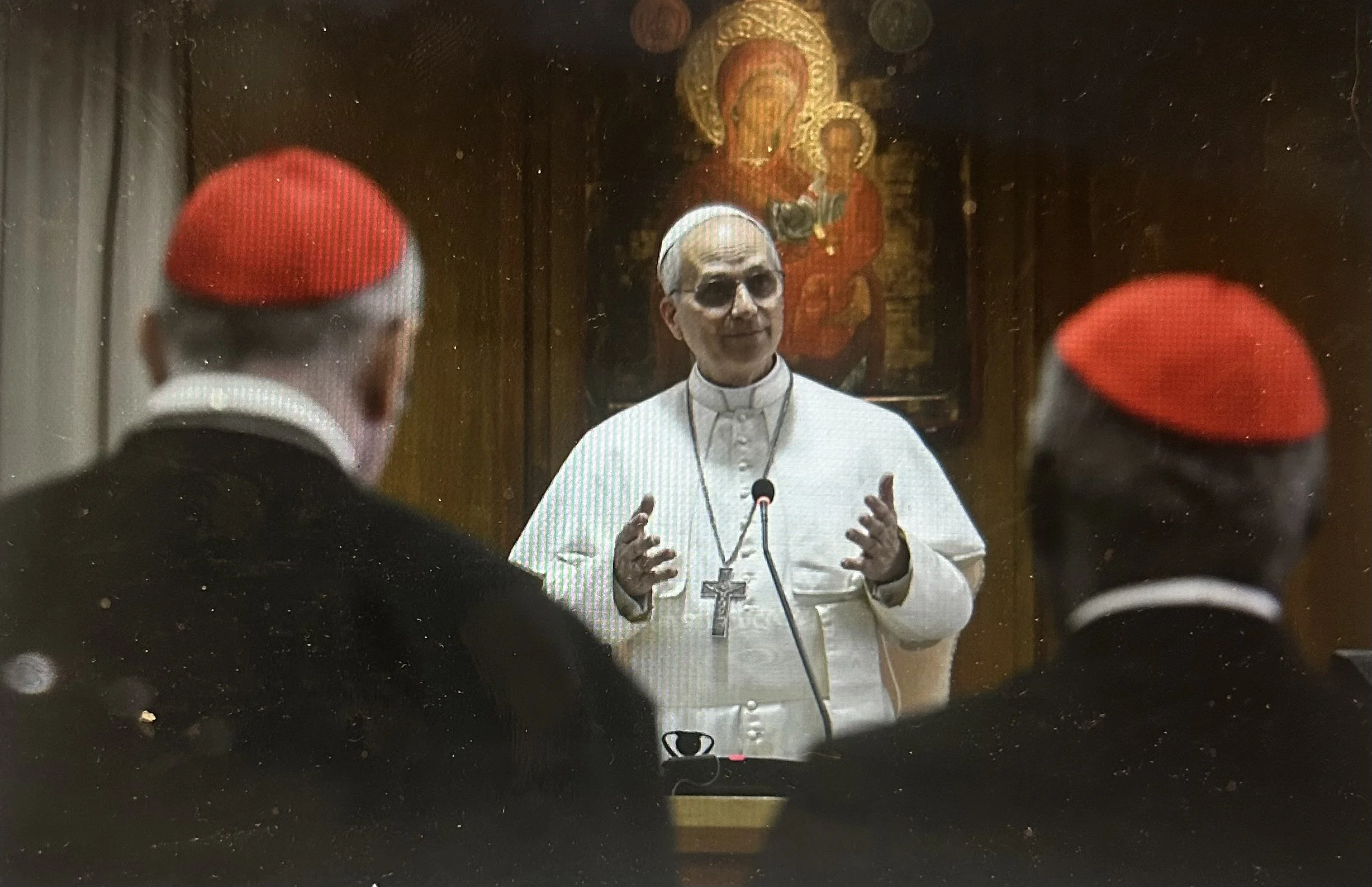

In his first meeting with cardinals after his election, Pope Leo XIV identified AI as one of the biggest challenges facing humanity.

An alternate policy path: But the institutions don’t have to merely respond to the crisis; the AI revolution is one that raises deep ethical considerations that faith institutions and some nonprofits might be able to speak to with valuable moral clarity. In some of his first comments after his election, Pope Leo XIV called out the challenges that AI poses to “human dignity, justice and labor” and signaled that the Catholic Church might be willing to be at the table as we try to build a moral consensus on how to deal with a new technology that, according to a Catholic advisory document earlier this year has no capacity “to savor what is true, good and beautiful.” The document calls on developers and users to take responsibility for ensuring that AI products aren’t used to deepen inequality, harm the environment or escalate the loss of life in war. But they aren’t fully equipped for that job: we need humans with experience working inside moral frameworks to help make decisions about key issues AI is raising:

· Where do we draw lines once we determine gene editing could be used to improve human intelligence or eradicate disease?

· Under what circumstances should we cede decisions about taking human life during war to AI?

· When should we let AI’s make decisions about health care treatment?

Vice President J.D. Vance and others have admitted that the US is not qualified to convene conversations about the ethical and moral issues AI raises, and has suggested that maybe the Catholic Church is. Other faith communities or nonprofits or philosophers or ethicists who are accustomed to operating in that sphere may also be able to help. There is a gaping opportunity for leadership, and it is unclear who else could play that role.

The challenge we face on the policy front is that, while the people developing the technology understand the importance of working with frenzy, those of us who will be affected by it don’t understand it well and are acting with caution.

“In the face of ginormous uncertainty,” Anton Korinek, an economist at the University of Virginia said to Axios this week, “one of the most common reactions is to wait and see.” But with the stakes as high as they are, he says, “That’s a pretty hazardous approach.”

Time’s a wasting’. Let’s jump on our tugboats.

Notes:

The Luddite rebellion: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luddite

The “technological security dilemma”:

https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/eat-your-ai-slop-or-china-wins

US Senate rejection of 10-year AI regulation moratorium: https://time.com/7299044/senators-reject-10-year-ban-on-state-level-ai-regulation-in-blow-to-big-tech/

Grade school and university reactions to AI: https://www.axios.com/2025/07/09/ai-rapid-change-work-school

Challenges of integrating AI into grade schools: https://www.nasbe.org/state-education-policy-and-the-new-artificial-intelligence/

California State makes Chat GPT available to all students: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/07/technology/chatgpt-openai-colleges.html

Universities integrating AI into curricula: https://news.vt.edu/articles/2025/04/provost-teaching-artificial-intelligence.html; https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/artificial-intelligence/2024/12/19

The humanities in time of AI: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-weekend-essay/will-the-humanities-survive-artificial-intelligence

Skills young graduates need: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/02/opinion/ai-human-education.html

One college learning proposal by Niall Ferguson in The Times: put university students in cloisters where they must operate without technology: https://www.thetimes.com/comment/columnists/article/ai-brain-robbery-universities-chatgpt-c6lr03dlz

The Vatican and technology: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2025/06/pope-leo-xiv-artificial-intelligence/683237/

VP Vance on moral leadership: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/21/opinion/jd-vance-pope-trump-immigration.html

Danger of not moving quickly on AI policy:

https://www.axios.com/2025/07/09/ai-rapid-change-work-school